Artist Eli Sobel works in many techniques and mediums including, drawing, ceramics and printmaking. His work is diverse and interesting . The one aspect of his art that I was most curious about was the fact that he does Installations. He creates Art installations in a space with wood, ceramics, prints and photographs. Eli was kind enough to spend time with me to answer all of my questions and and allow Eager to Know listeners to learn more about him.

Ricky McEachern (00:25): Artists, Eli Soble works in many techniques and mediums including drawing, ceramics and printmaking. His work is diverse and interesting. The one aspect of his art I was most curious about was the fact that he does installations. He creates art installations in a space with wood, ceramics, prints and photographs. Eli was kind enough to spend time with me to answer all of my questions and allow eager to know listeners to learn more about him.

Ricky McEachern (00:56): So a lot of the work that I saw that you were doing that you've done is around installations and most of the artists that I engage with aren't involved in that type of thing. They're all like painters. So they go to their studio and they paint something and then they sell it online. They sell it at a gallery, they sell it at an art show. And that's the general flow. What I saw for you was not that it was something different. So can you describe to me what, you know, what that is? Can you describe to me an installation, the intention and how that all works?

Eli Sobel (01:33): Sure. Usually the way installations come about as if I have this space and if I have the resources to uh, make something for that space, I see it as an alternative to having a white cube. So just putting a painting on the wall or drawing on the wall and sort of expecting that that's it. I sort of think of the stuff that has made as living. So even though you've let go of it and put it out into the world, it continues to have a life beyond the intention. So it may end up in a different area or, or a space. So by building an area for it, then at least it's some insulation. It's somewhat true to what I had envisioned cause it's, it's more temporary and fleeting. It's not meant to last forever. I guess I fell into doing installations at least for right now by starting out as a, as a painter. Um, so I went to art school as a painter in Maryland and it seemed initially it seemed very sort of still defined or I'm sort of locked in in one way of doing it. By doing installations. It broadened the realm of possibility for say what a painting could be or what a print could be. So are you feeling constrained? A little bit. Yeah.

Ricky McEachern (02:54): And so the first thing you mentioned in this process was the space. So does that come before the idea? Uh, like the creative inspiration or like does the actual space itself, um, is that the bud of the creative inspiration or do you have all of these ideas in your head and you're just looking for a space?

Eli Sobel (03:13): I've had both happen. So I had one project that I had brainstormed with a friend and the space happened to arise. And then there are other times where people had given me a space and then I had to come up with something for it. And that was a bit, there are times where that felt a bit more forced. In the first instance I had come up with a project where you have a darkened room and the only way that you can navigate is by touch. And that's by installing Bendis hers along the perimeter of the room so that you have to sort of follow that as a guide or a different Heights, different levels they break, they have different textures. So the guide itself is somewhat limited. So at some point you just let go and you're sort of floundering through the room and the space and hoping that in front of anyone else or bring yourself on a banister. Some of that project was constrained by the exhibition venue, so it was on a university campus. And because of that it had to be accessible to everyone. You couldn't hurt yourself in it. And um, it needed to have some sort of disclaimer and some of that affected the construction of how I did it.

Ricky McEachern (04:27): Okay. But the idea itself, was that something that you were trying to express something? Are you solving a problem? Like what Eli Sobel (04:36): in that case, I think it was trying to solve a problem. So trying to make something that you can't document, so something more can to an experience because each one, each person would, some go through it differently. And I, I know that happens with how you look at a painting and what's referenced with that. But with an installation it has more, I think more of an emotional or or sensorial impact.

Ricky McEachern (05:01): So you were looking to create something that was unique for everybody and had a sensory aspect to it? Yes. And where did that come from? I mean, it's a great idea. I think it's, I think it's fantastic. I reminded me of, I go to, um, so Cedar point, where are you from Afghan? Are you, where are you originally from? Oh, you're from me? Yeah. You're from Maine. Well, Cedar point's like this big amusement park here and it's the biggest amusement park in the world. Um, and at Halloween they have all these like fun houses. And I remember they had this special one where it was a dark room and you had to feel your way. It was pre, cause I saw your video of your thing and it was very similar and you had to feel your way around in order to get out of the room. And it was, but it was pitch black. And so that's what they were trying to create. They were trying to a sensory experience. It was going to be something that was as opposed to a normal fun house or spook house. It was different for every single person. So that makes sense for a amusement park. Um, it's interesting that that seems like a similar goal

Eli Sobel (06:13): for an art installation. Yeah. Um, I guess it came about by going to another school. So at the time I had been studying the U S and I tell you the, the U S education system is pretty classical and Western and I ended up in the Netherlands for a period of four months and that was quite different dynamic. You can envision, um, sort of the, the Bauhaus sort of the form over function or um, meeting black mountain college. So it was a school in North Carolina that had sort of performances and dance and scientists as well as, uh, Joseph Alvarez and uh, Rauschenberg. Uh, and then putting those two together, it created a very different dynamic. So I guess the way, another way to describe it as, uh, there were no formal classes. You had workshops, you could go in, you do whatever you want, but you figure out what you need to get the projects done. And that includes how you exhibit your work. So you find the venue or you make the venue and you make your work fit it somehow or not for that. So you have to focus on the light for the paint or how people enter this space. And that's not something that was necessarily considered when I was studying in the U S it was more about making work and then figuring out what it's about. \

Ricky McEachern (07:46): Maine, and I think you grew a screw up outside of Portland. So that's not the most, I mean, Portland is not a big city. Um, I think it's like the same size of like Providence, Rhode Island or Milwaukee, Wisconsin actually it's probably smaller than Milwaukee. I think it's smaller, but yeah, it's fatigued. Yeah. So it's small. And also Maine is somewhat of a, I mean, I love Maine. I think it's amazing. It's beautiful, but it's definitely not, it's not a place I could think of

Eli Sobel (08:16): art oriented. Yeah. I mean, I mean, how did that work for you growing up with this brain of yours? How did you end up in Maine being where you are now? I don't know. I mean, I started doing art because I had a lot of free time, some free time on my hands. There were no kids in my neighborhood. And Oh really? No, no. And it was just a small road and all the children had stood up by the time that we were sort of, my siblings and I were thinking, uh, and perceptive. Uh, they had all gone to college, so everyone was a retiree. So as a result, we spent a lot of time by ourselves. So we didn't play so much together and to commute to a friend's house, it could be half an hour or an hour. You'd have to get a car.

Eli Sobel (09:09): There's no public transportation, so I started spending a lot of time drawing just writing stories and I didn't have your iPad. I did not have an thank God, thank God you didn't have an iPad. My family also had a note TV rule as well for ear. It was probably probably smart, but yeah, so draw. So drawing and writing stories, did you say? Right. I mean they had us real cooking as well and spinning wall, which in retrospect is really strange. I've definitely talked with friends about it and they said, you haven't done that. Did you raise animals to know? Although I'm sure one of my parents would've loved to do that. I'm telling you this sounds like an idea like childhood. I mean I grew up in the suburbs of Boston and you're describing sounds amazing. I don't know. At times it felt as if it was the perfect prison because there's nowhere to go.

Eli Sobel (10:11): There was nowhere to go and there weren't really events to go to. Right. So we were both based in Chicago and usually there's always something. So there's rock and there is a event. Totally. But it sounds like in your case, you know, this sort of was, it caused you to create, to create, yeah. Yeah. So it caused me to create and I spent a lot of time doing these sort of summer art programs with my brother and sister. So it was easier for us all to do it together rather than do it separately. So we ended up doing stuff through one of the local museums. Okay. Portland museum of art and then a ceramics program from when we were I think nine until we were 16 or 17 and that was year round every week? No. Do your siblings, are they I'm in a creative field.

Eli Sobel (11:07): Yes and no. So I have a twin brother who's a mechanical engineer. So when I have a uh, older sister who was a reporter for an MPR affiliate, it is all, it is creative in different ways. So we're all creating content with them. They're there are solving problems. I'm the one still making them. So why do you feel like you're making problem? That's, so that's the, that's an interesting way of thinking about it because it's not offering us a solution, let's say with my brother, he's, um, he's making a product. Yeah. He's doing something to, to sell and to share and that fits a need. And it's the same with a, you're writing content for the times to inform, uh, over fishing or a rat that has been escaped in Alaska on a remote Island or a Japanese in invading part of Alaska during world war II. So it's, so it's all to fit a certain need and what I'm doing doesn't necessarily do that.

Ricky McEachern (12:21): See, that's interesting because I feel like as a painter, I feel like I am solving a problem. I feel like I am, I guess I've never really thought of it this way, but I do feel that I am taking something that's in the world that maybe others can't see. And I'm presenting it in a way that resonates with the, with the rest of the world and that they are like, Oh, okay, cool. That's great. I never thought of seeing something in that way. So I guess I sort of think of that as a problem solving exercise. And it sounds like what you're doing with these installations, it is not that, no.

Eli Sobel (13:00): And I guess I, I don't see it as necessarily solving, uh, providing an answer. It's, um, providing a vehicle to ask more questions. Okay. Maybe that's the equivalent of sort of, uh, kicking a can down the road. So not,

Ricky McEachern (13:21): does that leave you uneasy or unsatisfied or unfulfilled or is that something that leaves you feeling satisfied

Eli Sobel (13:30): and I guess it leaves me hungry, so it makes me, uh, uh, it, it makes me question more perhaps. Ricky McEachern (13:39): So it's like eating potato chips. Like, I mean, it's like the more potato chips you eat, the more you want. So it's kind of like that. So do you feel like that is something that is going to be sustainable, sustainable, moving forward for you?

Eli Sobel (13:56): Yeah, I think with installations, uh, it's just what I'm doing at this current juncture in time. I don't see myself doing that forever. Uh, and I can definitely see my work changing. Uh, I mean there are certainly things that I made a year ago that I cannot replicate now. I just was in a mindset and that's with drawings and prints and uh, I'm confident that what I make in the future will change as well. I mean, some of it is based off of the environment itself that I'm creating. So right now I'm in a basement filled with dog. I see a doc, a doc, yes. A dog and uh, lots of cans of paints. And I'm sure some of that will factor into what I will be making. Are you down there making something? Is that, is that like your studio? Yeah, it is my studio.

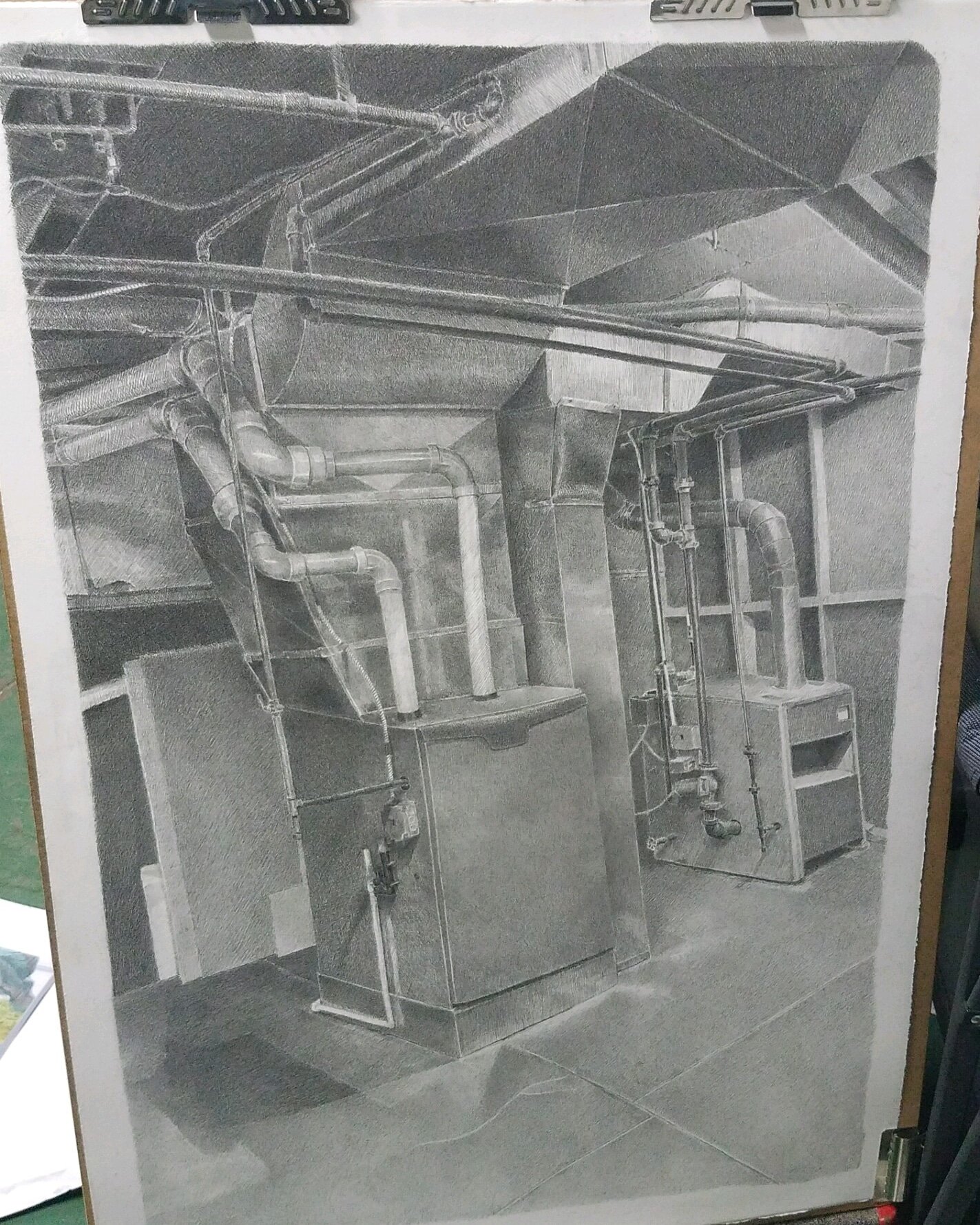

Eli Sobel (14:55): So I, I'm actually working on a drawing right now. Oh, cool. Trying to consolidate resources. Oh, nice. I am, I have a lot of time on my hands. So, so is that, uh, is that graphite? Yeah, so this is just a pencil drawing. That's amazing. Is that for down in the basement? Yeah. So I have spent a lot of time looking at the furnace, a water heater down here because I am trying to focus on, well inadvertently focusing on the things that I can be grateful for, such as shelter and electricity and sort of the bare necessities. Yeah, that's fantastic. Yeah, that's amazing.

Eli Sobel (15:42): So we'll see. I was hoping that I could have worked on this as long as the crisis persisted, but I suspect this started another project soon. A meeting. You think you're going to finish that and you're going to have more time? Yeah, yeah, yeah. Let's just draw myself out of the basement. But I think you should document the entire basement. I think that is your Corona virus project. I think it would be fascinating. Yeah. Well it probably will be stuff happening. Cool. So is there anything else that you want to share about your work or you know, anything that I didn't ask you? I know I asked you tons of questions. I might have one or two questions for you. That's her. You said you wanted to ask me questions. A question. I have for you is sort of a lot of people don't understand or don't appreciate that the difficulties that come into making a podcast.

Eli Sobel (16:42): And what's the hardest part for you for whether that's a developing questions or cutting audio or, the hardest part of it is, um, probably editing because I have to, I have to listen to the entire podcast a lot of times unfortunately. And it's, and you run out of steam? Um, I used to have somebody edit edit for me and I don't do that cause it's just, it's just easier and more efficient for me to do it myself. So for instance, if we're recording 45 minutes, um, I have to listen to the whole thing 45 minutes then without really taking any notes cause I have to understand the whole thing. Then I gotta go through it again and edit and clip and get rid of stuff. And then I got to clean stuff up and then I have to pull quote, I do like marketing materials with the quotes. So there's just a lot of stuff like that. The creative aspect of it is not hard. Like these conversations are very easy. And, um, booking guests is pretty easy. It's, it's really easy to

Ricky McEachern (17:50): find people. So, yeah. All right. And then thank you. I have two more, which are a little more out there, so, okay. What's something that you find yourself saying all the time, such as a CRA catchphrase? So for example, I say at least I still have my hair and teeth, so what's a thing that you might find yourself saying? At least I still have my teeth because I don't have my hair. Um, I would say, Oh goodness. Um, what do I say? I don't know if I say things, I may, I may think things, um, that, that I'm grateful for breathing and ha and being and having the use of my legs and arms. I think that all the time, I think of that all the time. When I was living in Boston, I used to go running all the time and I used to run down Massachusetts Avenue and it was this place where there were always people.

Ricky McEachern (18:57): I don't know what the building was, but there were always people out in wheelchairs. And oftentimes I would be in like a horrible, horrible mood and thinking that I had like the worst life ever and I would go running and I would see these people in wheelchairs and I'm like, okay, you're running and you have the ability to, you can move and you're not in a wheelchair and it would like readjust my thinking. So I think I think that a lot when I'm thinking that I have the worst situation in the world, which we all think, you know, sometimes. And I remind myself of that last question. Uh, if you were to give a book to anyone, what would that book be?

Ricky McEachern (19:40): If you were to walk in your apartment, grab a book off the shelf, throw it in the mail and let's see, it would either be Martha Stewart home keeping handbook, Martha Stewart print out this gigantic book. I haven't looked right here though. This probably might be one of them. It's basically a gigantic book that tells you everything you need to know about maintaining a home. And I keep it like I put my to do list is on top of that. So I would say either that or Mark, Mark Bittman's how to cook everything, which is a cookbook. So a, and that's, and that's a book that I give as a gift constantly cause it's a, um, it's a good starting. People are always saying that they weren't to learn how to cook and that's a great cookbook to start with. Wow. Okay. Wonderful. So neither one of them are that creative oriented, but

Eli Sobel (20:49): Oh no, I would say they're the absolutely creative. Yeah. Do you think the home keeping one is creative? Yeah. How you organize your space is really creative. Yeah. Ricky McEachern (21:03): And one of the great things that they have that she has in here is she has a T a task list of what you do every day, every week, every month and every season. And it's a checklist, a daily checklist. And I use it and it's, and if you do this, it basically keeps your entire house in pretty good shape if you, if you adhere to her, her schedule. Wow. Is it similar to the Marie condo or, I don't know. I don't know. Um, I think the Marie Kondo stuff is more about only having things that you value. Okay. And I haven't read her book, but from what I absorb, it's all about having less and having fewer things and only having things that you value. Whereas Martha's is more about, it's like a guide for the troops. For the military. It's, it's, it's more about rigor and, uh, you know, that's just kind of how her personality, but, you know, but I do like the having less, uh, you know, having only things that you value in your life I think is very important.

Eli Sobel (22:24): No, I think that's a good philosophy. Yeah, I would agree with that. So. Well,

Ricky McEachern (22:32): I'm out of questions. Okay. Well those were good questions, although I feel like I sort of derailed your first question, but, uh, but they were good. They're good questions.

Eli Sobel (22:43): You didn't derail them. So I was just trying to think of things that to ask because I, I'm curious about whoever's asking me questions. Yeah.

Ricky McEachern (22:59): Uh, well I am, Oh, I am always open to any questions you have. Okay. Well. Um, where can people learn more about what you're up to and see some of the stuff that you had been working on? Sure.

Eli Sobel (23:16): If anybody's interested in learning more about my work, they can check it out on my website, which is [inaudible] dot U S and how do you spell that? E. S O. B, E, L. And then period. And then you asked us, um, and I should have updates on my current projects and endeavors over the last four or five months in the next couple of weeks. Yeah. Okay, great. Yeah. Well thank you very much. It was great chatting with you. Thank you. It was nice chatting with you as well. Pleasure. All right.